Legal Determination of Conscientious Beliefs

Under the 1964 National Service Act (NSA) all males turning twenty in 1965 between 1 January and 30 June were required to register for National Service. All the birthdates for that period was represented by a marble which were placed in a barrel. A specified number of birthdate marbles were selected from the barrel. The required number of selected birthdates was dependent on how many men the army estimated they would need to train in order to fulfil their military commitments in Australia and overseas. The selective conscription process was repeated every 6 months until the newly elected Minister of Labour and National Service suspended the operation of the NSA in December 1972 by administrative action. In June 1973 the Commonwealth parliament passed the National Service Termination Act giving legislative effect to the administrative action.

Following the selection of a person’s birthdate he was required to attend a medical examination and an X-ray to determine his fitness for military service. Approximately 50% of young men the young men balloted in failed the medical. Those who passed the medical were next informed by the Commonwealth when they would be called-up and what military rank they would hold.

There was also a provision for a person balloted in to make application for deferment of being called-up. Completion of university and other types of educational qualifications were common examples as grounds for deferment. Continued deferment was conditional on successful completion of the relevant studies.

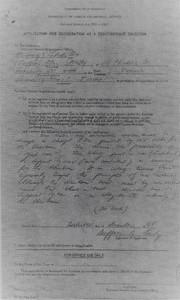

There was also provision for those who had passed the medical to then make application to be registered as a conscientious objector to serving in the military in any capacity or just for combatant duties.

Upon completing an application to be registered as a conscientious objector a date for a court hearing was communicated to the applicant. The legal arrangements differed among the states and territories of the Commonwealth. The court had to decide whether to grant a full exemption or exemption from combatant duties only or to dismiss the application. An applicant who failed to be granted the desired exemption had a right of appeal to a higher court. This could be exercised through multiple courts.

A person could transition from being a conscientious objector who complied with the NSA to a non-complier. This was common if a person’s application to be registered as a conscientious objector and the subsequent appeal were dismissed.

A common criticism of the court process was that the Commonwealth provided no clear criteria for the determination of whether an exemption should be granted or not. This proved a difficulty for both the state’s and the applicant’s legal personnel. It was also alleged that applicants in some states and territories had a better chance of success than in others because of the different court arrangements. The onus of proof was on the applicant, and the greatest chance of success was demonstrating that the conscientious belief was of long-standing.