The Second Phase: Civil Disobedience 1967-69

The second phase involved many antiwar groups and activists moving to the kind of civil disobedience and nonviolent direct action strategies that had worked so well in the US civil rights movement under the leadership of Martin Luther King. It was also a period of increasingly strident street protests, such as the 1968 July 4th antiwar demonstration at the US Consulate in Melbourne where some 4,000 protesters were involved in major confrontations with police (whose tactics included riding horses into the demonstrators).[8]

The impetus to this increased non-violent direct action on the part of the antiwar anti-conscription movement was the simple moral imperative of witnessing the daily mass slaughter of Vietnamese and feeling that you had to do everything you could, in a nonviolent way, to halt this appalling act of genocide. The stakes were so high in terms of the death and destruction in Vietnam that many in the antiwar and anti-conscription movement felt very justified in turning to active non-violent civil disobedience to alert the wider public to what was happening after the lack of success with conventional forms of protest in the lead up to the 1966 Election.

First draft resisters and anti-conscription civil disobedience

The year 1967 saw the first draft resisters refusing to comply with call up notices or medicals. They were inspired by the example of a Sydney school-teacher, Bill White, who, in late 1966, refused to be called up after being unsuccessful in a conscientious objection application.[9] It also saw the emergence of new anti-conscription strategies of nonviolent sit-ins and civil disobedience on the part of both existing anti-conscription groups, such as Save Our Sons, and newer ones, such as the Draft Resistance Movement, Students for a Democratic Society (at Melbourne, Latrobe and Sydney Universities), Students for Democratic Action (Brisbane), Monash Labor Club, and, later, the Draft Resisters’ Union.[10]

“We resist because…”

In April 1970, a number of non-compliers, including Brian Ross, Peter Hornby, Mike Matteson, Robert, Graham and David Mowbray, Geoff Mullen, Steve Townsend, Tony Dalton, Robert Hall and Michael Hamel-Green, circulated a pamphlet in April 1970 , “We resist because…” to voice our reasons for not complying with conscription.[11]

Michael Hamel-Green’s statement said:

Not with my life do you napalm women and children in Vietnam, burn down their flimsy huts and villages, deprive them of their future by backing a corrupt military dictatorship…Hundreds of young people in Australia are saying to the government: you will not terrorize us by the threat of two years’ gaol or the prospect of police clubbing. …There are those who tell us it is only self-destroying to throw ourselves on the cogs of the system. To them, I can only give the reply of Anouilh’s Antigone: ‘Whom do you want me to leave dying, while I turn away my eyes?’”[12]

In the pamphlet’s introduction, ABC broadcaster and film critic, Julie Rigg, noted: “I hope the actions of these men, in not complying with the Act, will help establish a new ‘right’ – the right of any individual to refuse to kill on behalf of the state, for any reason at all. For myself – I don’t think there’s a cause in the world that isn’t worth not killing for”.[13]

Initial gaol sentences

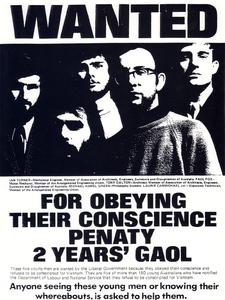

The period 1967-69 saw several draft resisters gaoled, including Simon Townsend, Dennis O’Donnell, Desmond Phillipson, John Zarb, and Brian Ross, all of whom became the focus for protests and demonstrations, particularly outside the walls of gaols where they were imprisoned. In subsequent years, Geoff Mullens, Bob Scates, Ken McLelland, Ian Turner, Robert Bisset, Mike Matteson and Gary Cook were to be gaoled for refusal of call up notices. [14]

As he was being sentenced to gaol, Geoff Mullens said to the court: “I am not a machine. I am not to be used as others will [in this war]. I can, as Bertrand Russell asked, ‘remember my humanity’. If you cannot, I pity you”.[15]